They believe that further decreasing their A1C level, down towards the non-diabetic range, will provide the most protection against diabetes-related complications, or perhaps even prevent them completely. Only a minority of patients with diabetes reach that benchmark, typically after considerable effort.īut a smaller minority of people with diabetes reason that an A1C just below 7.0 percent is just not good enough. Doing so without an unusual amount of glycemic variability (extreme blood sugar highs and lows) confers significant reductions in the risk of diabetic complications. It’s fair to say that most doctors will be pleased to see any of their (non-pregnant) patients with diabetes achieve an A1C at or just below 7.0 percent. For example, women who are pregnant or planning to become pregnant are advised to attempt much tighter blood glucose control, because we know that tighter A1C goals are correlated with fewer fetal complications. There may be other special factors at play, too. And, sad as it is to say, older patients may have less reason to worry about some of the slow-developing complications of diabetes, because they may not live long enough to suffer from them. This severe and immediate danger of low blood sugars may outweigh the long-term danger associated with chronic hyperglycemia. Elderly patients, for example, may be less capable of perceiving the symptoms of hypoglycemia. Older patients, or those that already have more serious health issues, may be advised to target less stringent glucose control. They also may have a better reason to do so: they know that they have decades of life with diabetes in front of them, an awfully long time to develop complications. Younger patients with fewer health issues are probably better equipped to set a lower A1C target and choose a more stringent regimen. In advising a certain A1C target, your doctor will attempt to balance your risk of hypoglycemia against your risk of hyperglycemia, among other factors. By contrast, a “less stringent” approach means a less intensive glucose control strategy, which necessarily entails higher blood sugars. The phrase “more stringent” here refers to a more rigid or demanding glucose control strategy, generally characterized by aggressive use of insulin and other glucose-lowering medications in order to keep a patient’s blood sugar closer to the non-diabetic range.

#Lower bound hgb a1c normal range how to

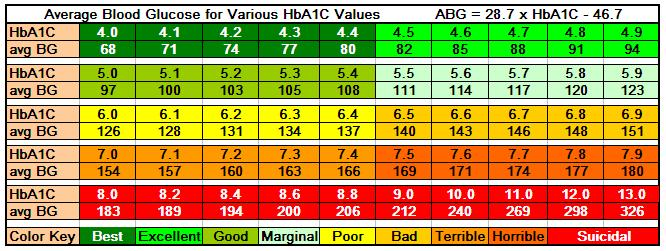

There is no official guidance on precisely how to weigh additional considerations, but the following image from the ADA gives an idea of how these different factors can influence glycemic targets: Making this adjustment can be more art than science, and is something best decided with the help of your primary care doctor or endocrinologist. This goal, however, may be adjusted based on several other factors. The ADA begins with a blanket recommendation for all adults with diabetes: aim for an A1C level of <7.0%. Readers that do not use either drug are at a significantly lower risk of hypoglycemia – much of the following discussion will not apply. This article is written for primarily people with diabetes, of any type, that use insulin or sulfonylureas, which are insulin mimetics. Higher A1C’s are correlated with a quicker onset and increased severity of complications, and it is well-known that lowering A1C correlates with decreased risks.

The American Diabetes Association categorizes blood sugars by A1C like so:įor the most part, everyone in the diabetes world agrees that a lower A1C is better than a higher one. It is still the most important benchmark for glucose management success, and is the primary way that your medical team will evaluate the success of your treatment. Your A1C is an estimate of your average blood sugar levels over the previous several months many people with diabetes are originally diagnosed with the results of an A1C test. Almost everyone who lives with diabetes is already familiar with the A1C test.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)